ISKCON–Shattered by Abuse of Children in Gurukuls [Boarding Schools]

In October 2001, 91 plaintiffs in their late 20s and early 30s filed a four hundred million dollar lawsuit in a Texas district court against more than a dozen Hare Krishna temples and organizations and many former leaders of the movement. The suit alleges that horrendous sexual and physical abuse occurred in at least eight of 11 Hare Krishna boarding schools in the 1970s and ’80s.

The appalled movement elders, who had learned of the abuse five years earlier, did not dispute the claims. But they argued that since the boarding schools were now closed (some because of the abuse, some because they were too costly to run), it would be unfair to force the movement to sell off major assets in order to placate the young people over events that had taken place 20 or 30 years ago. Instead, the Krishnas announced in February that the temples named in the suit would file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. This would effectively stop the legal proceeding.

Instead of using their limited resources to fight the suit, the Krishnas could establish a fund for the children who’d suffered. The victims of the abuse were undeterred, unwilling to paper over the deep rift that had formed between the generations.

The International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), founded in New York in 1966 and known as the Hare Krishna movement, once held a powerful appeal for youth disillusioned by American society and the Vietnam War. By the early 1970s, several thousand young people had given up everything to follow Srila Prabhupada, the movement’s elderly founder, and build temples and farm ashrams across America and later in Europe and South America. By joining the Hare Krishnas, they became members of a strict Hindu congregation that had originated in India. They shaved their scalps and wore fluttering orange robes, they worshiped Krishna over all other Hindu gods, they followed scriptures written thousands of years before Jesus and aspired to live simply and without material attachment, as prescribed in the Vedic scriptures.

It was so simple then. A 23-year-old from Mississippi named True Dianne Faust felt the same aversion to the American mainstream as the disaffected young devotees. Faust ran into a band of Hare Krishnas in downtown Dallas in 1971. As she stood there, rapt, in her hippie clothes, everything just clicked for her. Other devotees describe that moment as “walking through a wall of water.”

At that time, the movement was just 6 years old and its leader had already made a name for himself. Prabhupada’s translations of the Bhagavad Gita and other sacred texts were widely respected and used for college courses. He’d grown close to John Lennon and George Harrison, who donated a 17-acre estate outside London to the movement in the early 1970s. The Krishnas purchased large tracts of land in West Virginia and Pennsylvania, a building in midtown Manhattan and nearly a block of Watseka Avenue in Los Angeles-largely with money from the sales of Prabhupada’s translations, which also fueled a successful book publishing business.

By the time Prabhupada blessed a bowing Faust and renamed her Bimala–which means spotlessness in Sanskrit his movement was opening nearly a dozen new temples each year in American cities. (At its height, there were almost 10,000 devotees living in the temples and on the farms.) Bimala initially shared a bedroom in the Dallas temple with her husband and two other young couples. She went to ritual ceremonies at the temple’s altar, beginning at 4:30 a.m., attended daily scripture class and chanted for the requisite hour and a half.

Bimala started typesetting and designing little booklets that her “godbrothers” pressed into people’s hands at airports. Work was unpaid, in the service of Krishna. She lived and ate at the temples and if she needed anything extra, such as toothpaste or tampons, she’d ask the temple treasurer to add it to his shopping list. The mundane things of life–tax returns, grocery shopping, career, even news from the ongoing war–had ceased to be a concern. Being a full-time monk was far more meaningful, she thought, than her former job teaching junior high school English. This life seemed like bliss.

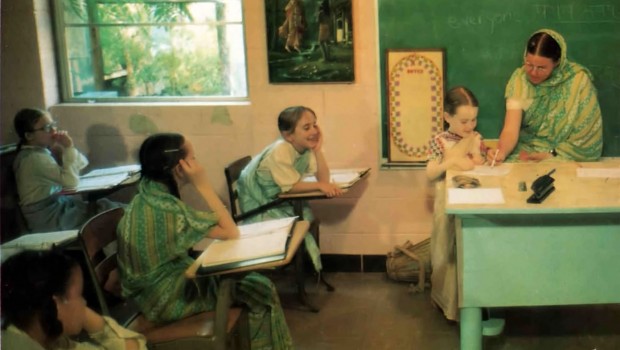

In that same submissive spirit, Bimala sent her 5-year-old son, Ish, to a Hare Krishna school in 1977. “It hurt to be separated from him,” she says, “but it was just what you did in those days.” The schools, scattered across the country and in India, combined round-the-clock child care with spiritual training. The idea was to keep the children safe from the influences of the outside world while their parents were freed up to work for the movement.

In Autumn of that year, the movement fell into crisis when Prabhupada died at age 81. In his will, he’d appointed 11 loyal young men to take over for him. Each was to run a zone of the country, in which he would be responsible for the welfare of all devotees. These “zonal gurus” reported to a board of directors, called the Governing Body Commission (GBC). Unfortunately, the personal qualities that attracted devotees to Prabhupada’s movement-and his strict daily regimen of rituals and work-were not necessarily leadership assets. His followers, finding themselves without a spiritual guide, had difficulty maintaining the Eastern structure of gurus and disciples that Prabhupada had established. Bill Ogle, 54, a former GBC member, noticed it right away. “You have some guy from Los Angeles who grew up surfing and went to a university,” says Ogle, in his smooth, Southern drawl, of one of the successors. “He’s thirty years old and he’s been a devotee for five or six years and suddenly he’s an enlightened guru? It’s just farcical.”

Ogle, then head of the Atlanta temple where he lived with his wife and young daughter, saw difficulties ahead in raising a family within the ISKCON structure, which was geared to single devotees and led by celibate men who were both zealous and inexperienced. “Economically the society couldn’t support everybody anymore.

As you got married and had children, your costs increased tremendously. It just wasn’t reality,” he says. “There was a lot of idealism, and there still is in the minds of many of the devotees, but realistically, people like me needed to find a way to live in the larger society.” So Ogle, while remaining a devotee, went off to law school.

In the next few years, tensions rose within many major temples. Some gurus became autocrats, harshly intolerant of any deviation from the rituals; others buckled under the stress of trying to keep their ashrams alive. Families found themselves unwelcome; children were expected to behave within the temples as little adults. One vocal dissident was found dead on the grounds of a West Virginia temple called New Vrindaban and, in 1990, the zonal guru there, Kirtanananda, was charged with using murder, kidnapping and fraud to protect an illegal enterprise (he was selling caps and T-shirts with pirated NFL and “Peanuts” logos).

By the 1990s, people were trickling away. Those who remained realized they had to learn to co-exist with the mainstream. Ogle’s friend, David Roberts, had spent most of his 20s and 30s as a Krishna missionary to Brazil. He took a job delivering newspapers at 2 a.m. before he found work running a small manufacturing firm. Roberts was then almost 40 years old; like others in the movement, he had no formal work history and he’d never even owned a credit card. “People returned, thinking, I gave my life to the mission and I don’t have anything now. What am I going to do?” Roberts says.

Some devotees hung on in the temples, selling books, but most moved on with their lives–returning to the degrees they’d abandoned, training as nurses and teachers. Bimala ran a computer store in Pennsylvania, then began designing silver jewelry. Ogle set up a successful law practice in Ormond Beach, Florida. Many of those who pulled away kept a connection to the movement, building shrines in their homes, donating money, chanting at the temples on Sundays or major Hindu holidays.

Their hard-won maturity actually advanced the movement. In Philadelphia, David Dobson took the local Hare Krishnas away from bookselling and missionary work and into Food for Life, the Krishna’s global social service organization. Dobson, 48, a slight, frizzy-haired man with boundless energy, was a member of a small group that set up a soup kitchen in a storefront near Philadelphia’s city hall. He also drove to deserted areas of the city with his portable stove to cook for the homeless. In the mid-1980s he won city contracts to open homeless shelters, and in 1991, he persuaded the state to fund a halfway house where he and other Krishnas helped ex-convicts ease back into society.

Dobson’s chapter of Food for Life, incorporated in 1983, has grown into a full-fledged agency that receives several million dollars in funding a year from the government. Dobson has proven so adept a manager that city officials treat his group no differently from Catholic Charities or Volunteers of America.

“We had to go from being a missionary movement to an institution,” Dobson explains. “There’s been internal soul-searching about how to do this and to keep the integrity and purity of the religious tradition and not water it down to attract new members or revenue.”

The movement’s new stability began to waver in 1996, when some grown members of the “second generation”-as the children of devotee baby boomers call themselves-asked to speak before a meeting of the GBC in Alachua, Florida, the largest Hare Krishna community in the U.S. Several hundred families live in and around Alachua, reintegrated into regular society around a modified temple (leaders are elected, not appointed; there is no ashram). Real estate is cheap; most of the families were able to buy modest ranch homes in the neighborhoods that have sprung up among the old horse and cattle ranches. They work regular jobs and shop at Food Lion like everyone else.

Standing on the temple’s marble floor, these young adults told stories of their school days. They described the emotional devastation of being separated from their parents at age 5, as well as being regularly beaten, terrorized and preyed upon sexually by teachers night after night.

The teachers, untrained and uncertified, lived with them 24 hours a day. Both girls and boys were raped and forced into sexual situations; girls as young as 12 or 13 were “given” to older men in the movement; one boy was raped by at least 10 different men. If they wet their beds, their faces were rubbed in the dirty bedding; if they soiled their underwear, they had to wear it on their heads.

Larry Shinn, president of Berea College in Kentucky, has studied the Hare Krishnas for 20 years, and he attributes what happened in their schools to the fact that the teachers were “young celibate men with an overabundance of enthusiasm about religious teachings and much less knowledge of child psychology or the emotional needs of children.” The cruel behavior that resulted has similarities to that in the Catholic Church; in both situations, Shinn says, “monastic males took advantage of their position of authority to abuse young boys.” As he sees it, this particular kind of abuse occurs “throughout the world.” In the ensuing two years, hundreds came forward to testify, and the newly formed child protection office found itself with a list of almost 250 suspected sex offenders. Dhira Govinda, the office’s director, soon learned that many perpetrators had fled the movement and that the statute of limitations prevented prosecution in most cases. Still, he was instrumental in getting several separate convictions of abuse. In 1996, another organization, Children of Krishna, began doling out grants for therapy and college tuition to the second generation and educating temple presidents on ways to prevent child abuse.

The elders feel strongly that they worked to heal the children as soon as they found out what had happened. There was no cover-up. But the members of the second generation were unappeased and filed the civil lawsuit that is now pending.

The depth of their bitterness has something to do with the fact that many are only now beginning to deal with the events of the past. Just like the abused Catholic children, they were too self-doubting and guilt-ridden, too scared to speak out against the authority figures who’d molested them. Jahnavi, 30, the director of Children of Krishna, explains: “When you don’t know anything about the world, it’s hard to recognize you’ve been abused,” she says. “Then at 30, you finally understand that your childhood was robbed and you get angry that you also spent most of your twenties trying to deal with your pain. And you’ve got this voice inside your head screaming at you all the time.”

As their pain surfaced, it took the form of fury at the adults for failing to protect them. “I blame them for setting up the structure that allowed the abuse,” says Jahnavi. “Parents were naive and trusted people, who on the surface, spiritually, were doing all the right things,” says Sad Krueger, 27, a fellow devotee and friend of Bimala’s son, Ish.

In the living room of Ish’s yellow ranch house on one of Alachua’s new cul-de-sacs, Ish and his mother talk over everything that happened. Bimala flips through a photo album to find a snapshot of Ish in 1983, the “zealous days.” There he is-a 10-year-old boy, freckled and grinning in a white robe with a shaved head. That year, Ish’s teacher-someone Bimala knew and respected-sexually abused him on many occasions. As soon as Bimala found out about it, in 1986, she put him in a public school and arranged for therapy for her son and herself.

Unlike many of the baby boomers, Bimala says she understands the anger that led to the lawsuit and acknowledges her own guilt. “I’ve cried for years and years over what happened,” Bimala says. “But at least I can talk about it now. There are other women around here who can’t.” Women’s “inferior role” in the Krishna movement, Shinn points out, had a harmful effect. As in other male-dominated religions, the women had to accept the movement’s practices unquestioningly, making the children’s disclosures even harder to handle.

Pranada, 44, has a 24-year-old son who lost his front teeth as a child after being slammed to the floor by a teacher. Like many other mothers, Pranada chose to ignore the signs of abuse. Faced with the revelations, “we were in tears,” she says, “and just dumbfounded that these things had happened.” She feels desperately guilty, she says, for sending her little boy away but is deeply opposed to the lawsuit, insisting it’s wrong to hold the system liable for the actions of individuals. That position disturbs the younger generation. Over 6 feet tall, with a trim beard and thoughtful manner, Ish is 28 and a lab technician at the University of Florida. He and many of his peers remain committed but casual Hare Krishnas. Being close to his mother, he says, helps him deal with mistakes made by her generation. “I went through some intense feelings as a kid–loneliness, really intense isolation,” says Ish. “But now I have an appreciation that all these things wrapped up together make you who you are. Sure, I wish that things didn’t happen the way they did, but I am happy with who I am now. I like to consider myself lucky. Other people had it far worse.”

Ish knows of former classmates who committed suicide and others who are emotionally crippled, so he supports those who filed the lawsuit, though he didn’t join them. He and his friends attribute the abuse to the older generation’s “hard-core philosophy.” They don’t want to destroy the movement, but they do want to clear out the cliche-spouting devotees, those “still on their trip.” “We’ve already had one set of victims come through-the kids,” he says, “and now it’s almost like irony that a lot of people are looking to create a whole new set of victims-those [baby boomers] who gave up their lives for the Hare Krishnas,” he says. “Some in my generation are saying, `Let them be. They’re not our responsibility. They didn’t stick up for us.'”

As of April, the lawsuit was still pending. The older generation, complaining about the “unfocused anger” of the children, has tried to avoid selling temple assets. They dissolved the Alachua foundation, and ISKCON’s press office sent word to newspapers to expect bankruptcy filings. But the far-reaching apology the younger generation craves seems unlikely to come from this court action.

“The way it’s being fought is really unfair,” says Dobson, who sees the bankruptcy strategy as a necessary act of self-defense. “The serious allegations should go through the criminal justice system. The society can’t be responsible for everything that goes on.”

Ogle, a defendant in the lawsuit because he was on the GBC board when the Krishna schools operated, says the victim’s rage is justified but misdirected. “I don’t think that the society as a whole was at fault, even though some of them see it that way. As some of them mature, they will see that it wasn’t.”

Maybe, maybe not. Ish almost never visits the lovely marble temple in Alachua that sits on a small rise shaded by live oak trees, where you can hear the rhythmic beat of drums and a harmonium throughout the day. In the faces of some of the older generation who worship there Ish does not see peaceful spirituality. He sees harshness and disapproval, and he can’t stay long before the bad memories return.